10-8. A Complete Example

In the preceding sections numerous concepts were introduced and illustrated, but the analysis was broken into disjoint pieces by sections. In this section we will go through a complete example of the use of correlation and regression analysis of data from start to finish, touching on all the topics of this chapter in sequence.

In general educators are convinced that, all other factors being equal, class attendance has a significant bearing on course performance. To investigate the relationship between attendance and performance, an education researcher selects for study a multiple section introductory statistics course at a large university. Instructors in the course agree to keep an accurate record of attendance throughout one semester. At the end of the semester 26 students are selected a random. For each student in the sample two measurements are taken: x , the number of days the student was absent, and y , the student’s score on the common final exam in the course. The data are summarized in Table 10.4 "Absence and Score Data".

Table 10.4 Absence and Score Data

Absences

Score

Absences

Score

x

y

x

y

2

76

4

41

7

29

5

63

2

96

4

88

7

63

0

98

2

79

1

99

7

71

0

89

0

88

1

96

0

92

3

90

6

55

1

90

6

70

3

68

2

80

1

84

2

75

3

80

1

63

1

78

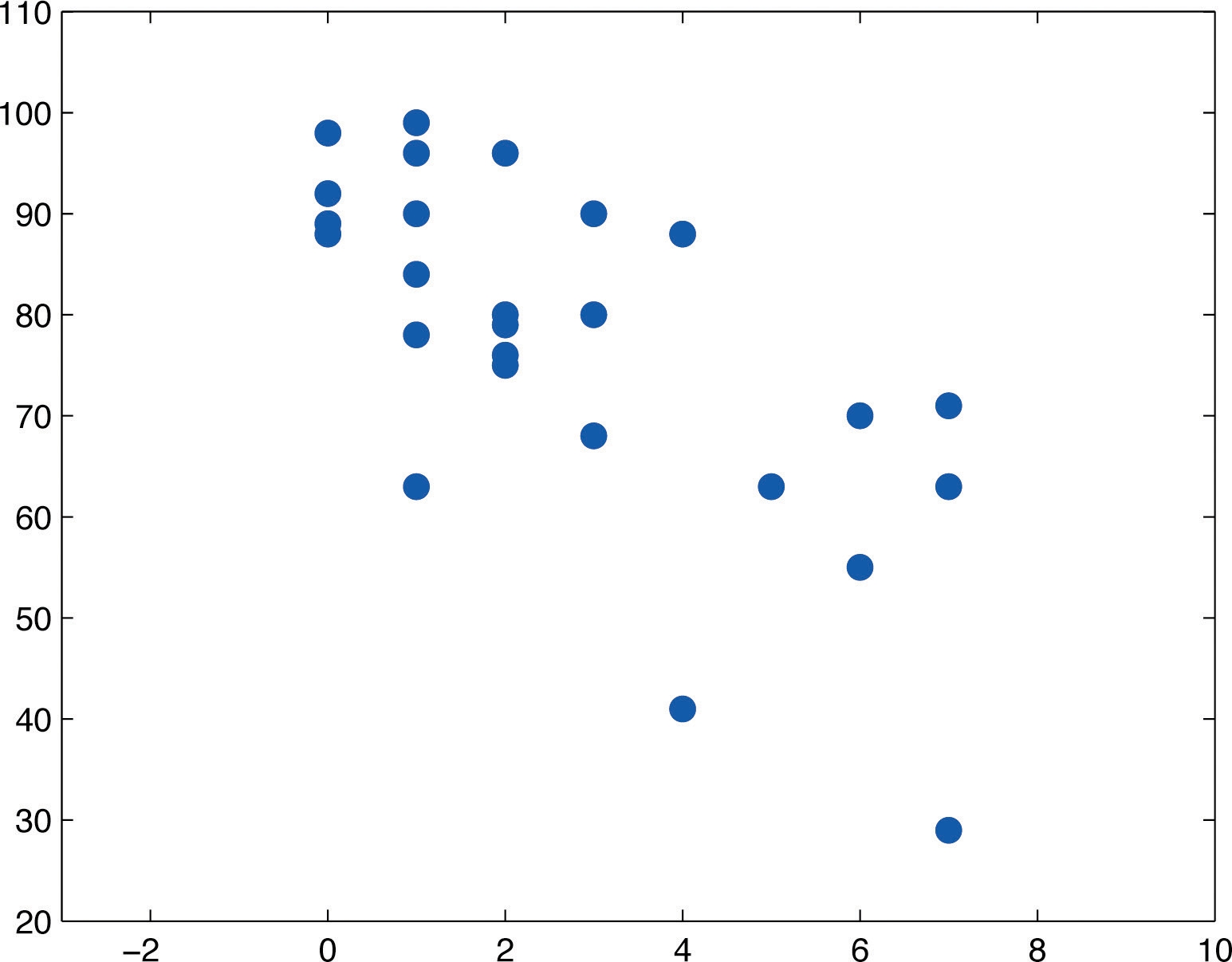

A scatter plot of the data is given in Figure 10.13 "Plot of the Absence and Exam Score Pairs". There is a downward trend in the plot which indicates that on average students with more absences tend to do worse on the final examination.

Figure 10.13 Plot of the Absence and Exam Score Pairs

The trend observed in Figure 10.13 "Plot of the Absence and Exam Score Pairs" as well as the fairly constant width of the apparent band of points in the plot makes it reasonable to assume a relationship between x and y of the form

y=β1x+β0+ε

where β1 and β0 are unknown parameters and ε is a normal random variable with mean zero and unknown standard deviation σ . Note carefully that this model is being proposed for the population of all students taking this course, not just those taking it this semester, and certainly not just those in the sample. The numbers β1, β0, and σ are parameters relating to this large population.

First we perform preliminary computations that will be needed later. The data are processed in Table 10.5 "Processed Absence and Score Data".

Table 10.5 Processed Absence and Score Data

x

y

x2

xy

y2

x

y

x2

xy

y2

2

76

4

152

5776

4

41

16

164

1681

7

29

49

203

841

5

63

25

315

3969

2

96

4

192

9216

4

88

16

352

7744

7

63

49

441

3969

0

98

0

0

9604

2

79

4

158

6241

1

99

1

99

9801

7

71

49

497

5041

0

89

0

0

7921

0

88

0

0

7744

1

96

1

96

9216

0

92

0

0

8464

3

90

9

270

8100

6

55

36

330

3025

1

90

1

90

8100

6

70

36

420

4900

3

68

9

204

4624

2

80

4

160

6400

1

84

1

84

7056

2

75

4

150

5625

3

80

9

240

6400

1

63

1

63

3969

1

78

1

78

6084

Adding up the numbers in each column in Table 10.5 "Processed Absence and Score Data" gives

Σx=71, Σy=2001, Σx2=329, Σxy=4758, and Σy2=161511.

Then

SSxx=Σx2−n1(Σx)2=329−261(71)2=135.1153846 , SSxy=Σxy−n1(Σx)(Σy) =4758−261(71)(2001)=−706.2692308 SSyy=Σy2−n1(Σy)2=161511−261(2001)2=7510.961538

and

xˉ=nΣx=2671=2.730769231 and yˉ=nΣy=262001=76.96153846

We begin the actual modelling by finding the least squares regression line, the line that best fits the data. Its slope and y-intercept are

β1^=SSxxSSxy==135.1153846−706.2692308=−5.227156278 β0^=yˉ−β1^xˉ=76.96153846 −(−5.227156278)(2.730769231) =91.23569553

Rounding these numbers to two decimal places, the least squares regression line for these data is

y^=−5.23 x+91.24.

The goodness of fit of this line to the scatter plot, the sum of its squared errors, is

SSE=SSyy−β1^SSxy =7510.961538−(−5.227156278)(−706.2692308) =3819.181894

This number is not particularly informative in itself, but we use it to compute the important statistic

sε=n−2SSE=243819.181894=12.11988495

The statistic sεsε estimates the standard deviation σ of the normal random variable ε in the model. Its meaning is that among all students with the same number of absences, the standard deviation of their scores on the final exam is about 12.1 points. Such a large value on a 100-point exam means that the final exam scores of each sub-population of students, based on the number of absences, are highly variable.

The size and sign of the slope β1^=−5.23 indicate that, for every class missed, students tend to score about 5.23 fewer points lower on the final exam on average. Similarly for every two classes missed students tend to score on average 2×5.23=10.46 fewer points on the final exam, or about a letter grade worse on average.

Since 0 is in the range of x-values in the data set, the y-intercept also has meaning in this problem. It is an estimate of the average grade on the final exam of all students who have perfect attendance. The predicted average of such students is β0^=91.24 .

Before we use the regression equation further, or perform other analyses, it would be a good idea to examine the utility of the linear regression model. We can do this in two ways: 1) by computing the correlation coefficient r to see how strongly the number of absences x and the score y on the final exam are correlated, and 2) by testing the null hypothesis H0:β1=0 (the slope of the population regression line is zero, so x is not a good predictor of y ) against the natural alternative Ha:β1<0 (the slope of the population regression line is negative, so final exam scores y go down as absences x go up).

The correlation coefficient r is

r=SSxx⋅SSyySSxy=(135.1153846)(7510.961538)−706.2692308=−0.7010840977

a moderate negative correlation.

Turning to the test of hypotheses, let us test at the commonly used 5% level of significance. The test is

H0:β1=0 vs. Ha:β1<0 @ α=0.05

From Figure 12.3 "Critical Values of ", with df=(26−2)=24 degrees of freedom t0.05=1.711 , so the rejection region is (−∞,−1.711] .

The value of the standardized test statistic is

to=(β1^−B0)/SSxxsε=(−5.227156278−0)/135.115384612.11988495=−5.013

which falls in the rejection region. We reject H0 in favor of Ha . The data provide sufficient evidence, at the 5% level of significance, to conclude that β1 is negative, meaning that as the number of absences increases average score on the final exam decreases.

As already noted, the value β1=−5.23 gives a point estimate of how much one additional absence is reflected in the average score on the final exam. For each additional absence the average drops by about 5.23 points. We can widen this point estimate to a confidence interval for β1. At the 95% confidence level, from Figure 12.3 "Critical Values of " with df=(26−2)=24 degrees of freedom, tα∕2=t0.025=2.064 . The 95% confidence interval for β1 based on our sample data is

β1^±tα∕2SSxxsε=−5.23±2.064 135.115384612.11988495=−5.23±2.15

or (−7.38,−3.08). We are 95% confident that, among all students who ever take this course, for each additional class missed the average score on the final exam goes down by between 3.08 and 7.38 points.

If we restrict attention to the sub-population of all students who have exactly five absences, say, then using the least squares regression equation y^=−5.23x+91.24 we estimate that the average score on the final exam for those students is

y^=−5.23(5)+91.24=65.099

This is also our best guess as to the score on the final exam of any particular student who is absent five times. A 95% confidence interval for the average score on the final exam for all students with five absences is

yp^±tα∕2 sε n1+SSxx(xp−xˉ)2 =65.09±(2.064)(12.11988495)261+135.1153846(5−2.730769231)2 =65.09±25.015442540.0765727299 =65.09±6.92

which is the interval (58.17,72.01). This confidence interval suggests that the true mean score on the final exam for all students who are absent from class exactly five times during the semester is likely to be between 58.17 and 72.01.

If a particular student misses exactly five classes during the semester, his score on the final exam is predicted with 95% confidence to be in the interval

yp^±tα∕2 sε 1+n1+SSxx(xp−xˉ)2 =65.09±(2.064)(12.11988495)1+261+135.1153846(5−2.730769231)2 =65.09±25.015442541.0765727299 =65.09±25.96

which is the interval (39.13,91.05). This prediction interval suggests that this individual student’s final exam score is likely to be between 39.13 and 91.05. Whereas the 95% confidence interval for the average score of all student with five absences gave real information, this interval is so wide that it says practically nothing about what the individual student’s final exam score might be. This is an example of the dramatic effect that the presence of the extra summand 1 under the square sign in the prediction interval can have.

Finally, the proportion of the variability in the scores of students on the final exam that is explained by the linear relationship between that score and the number of absences is estimated by the coefficient of determination, r2. Since we have already computed r above we easily find that

r2=(−0.7010840977)2=0.491518912

or about 49%. Thus although there is a significant correlation between attendance and performance on the final exam, and we can estimate with fair accuracy the average score of students who miss a certain number of classes, nevertheless less than half the total variation of the exam scores in the sample is explained by the number of absences. This should not come as a surprise, since there are many factors besides attendance that bear on student performance on exams.

Last updated