11-1. Chi-Square Tests for Independence

In previous chapters you saw how to test hypotheses concerning population means and population proportions. The idea of testing hypotheses can be extended to many other situations that involve different parameters and use different test statistics. Whereas the standardized test statistics that appeared in earlier chapters followed either a normal or Student t-distribution, in this chapter the tests will involve two other very common and useful distributions, the chi-square and the F-distributions.

The chi-square distribution arises in tests of hypotheses concerning the independence of two random variables and concerning whether a discrete random variable follows a specified distribution.

The F-distribution arises in tests of hypotheses concerning whether or not two population variances are equal and concerning whether or not three or more population means are equal.

11.1 Chi-Square Tests for Independence

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To understand what chi-square distributions are.

To understand how to use a chi-square test to judge whether two factors are independent.

1. Chi-Square Distributions

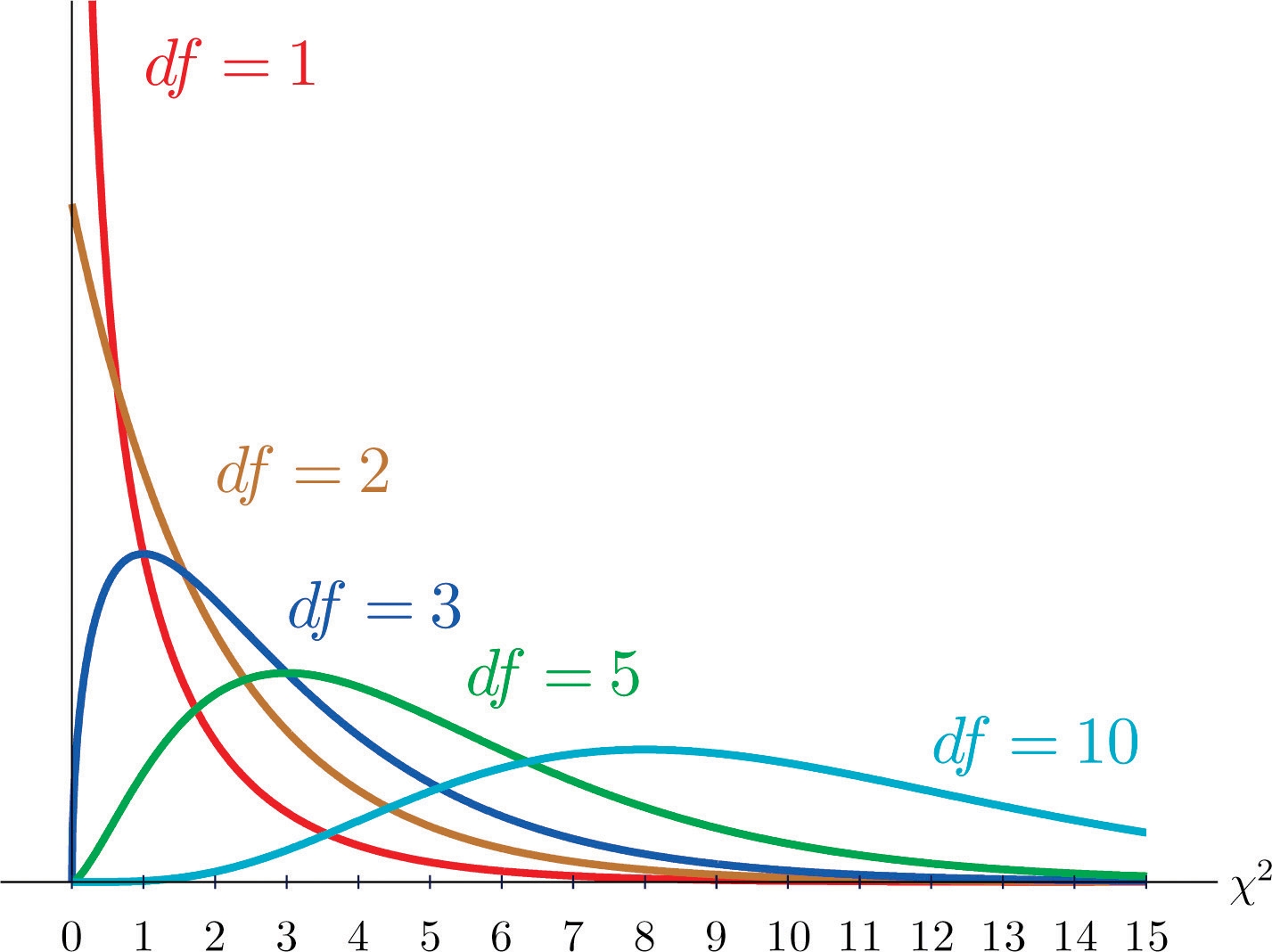

As you know, there is a whole family of t-distributions, each one specified by a parameter called the degrees of freedom, denoted df . Similarly, all the chi-square distributions form a family, and each of its members is also specified by a parameter df , the number of degrees of freedom. Chi is a Greek letter denoted by the symbol χ and chi-square is often denoted by χ2 .

Figure 11.1 "Many " shows several chi-square distributions for different degrees of freedom. A chi-square random variable is a random variable that assumes only positive values and follows a chi-square distribution.

Figure 11.1 Many χ2 Distributions

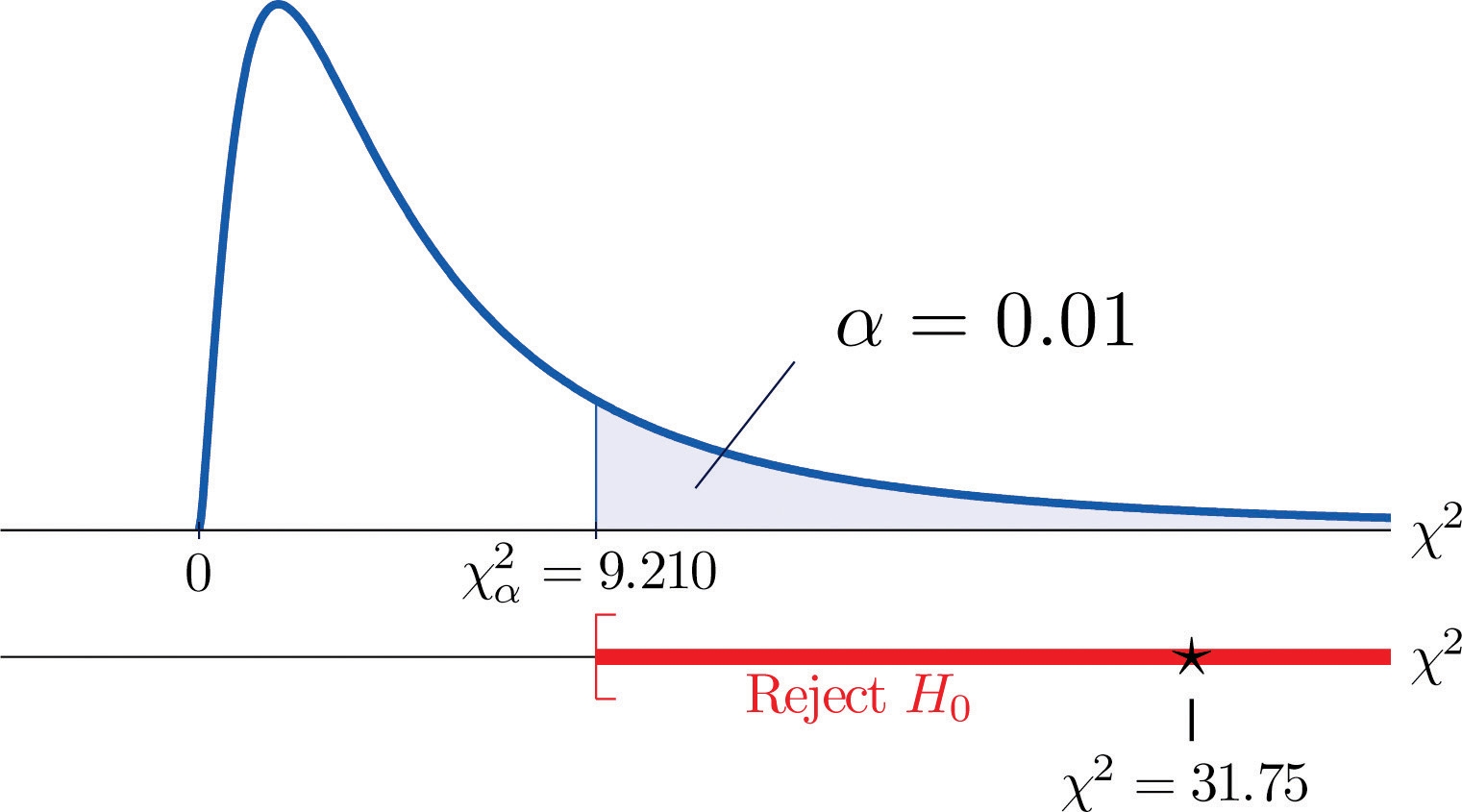

The value of the chi-square random variable χ2 with df=k that cuts off a right tail of area c is denoted χc2 and is called a critical value. See Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2 χc2 Illustrated

Figure 12.4 "Critical Values of Chi-Square Distributions" gives values of χc2 for various values of c and under several chi-square distributions with various degrees of freedom.

2. Tests for Independence

Hypotheses tests encountered earlier in the book had to do with how the numerical values of two population parameters compared. In this subsection we will investigate hypotheses that have to do with whether or not two random variables take their values independently, or whether the value of one has a relation to the value of the other.

Thus the hypotheses will be expressed in words, not mathematical symbols. We build the discussion around the following example.

There is a theory that the gender of a baby in the womb is related to the baby’s heart rate: baby girls tend to have higher heart rates. Suppose we wish to test this theory. We examine the heart rate records of 40 babies taken during their mothers’ last prenatal checkups before delivery, and to each of these 40 randomly selected records we compute the values of two random measures: 1) gender and 2) heart rate.

In this context these two random measures are often called factors. Since the burden of proof is that heart rate and gender are related, not that they are unrelated, the problem of testing the theory on baby gender and heart rate can be formulated as a test of the following hypotheses:

H0:Baby gender and baby heart rate are independent vs. Ha:Baby gender and baby heart rate are not independent

The factor gender has two natural categories or levels: boy and girl. We divide the second factor, heart rate, into two levels, low and high, by choosing some heart rate, say 145 beats per minute, as the cutoff between them. A heart rate below 145 beats per minute will be considered low and 145 and above considered high. The 40 records give rise to a 2 × 2 contingency table.

By adjoining row totals, column totals, and a grand total we obtain the table shown as Table 11.1 "Baby Gender and Heart Rate". The four entries in boldface type are counts of observations from the sample of n = 40. There were 11 girls with low heart rate, 17 boys with low heart rate, and so on. They form the core of the expanded table.

Table 11.1 Baby Gender and Heart Rate

Heart Rate

Gender

Low

High

Row Total

Girl

11

7

18

Boy

17

5

22

Column Total

28

12

Total = 40

In analogy with the fact that the probability of independent events is the product of the probabilities of each event, if heart rate and gender were independent then we would expect the number in each core cell to be close to the product of the row total R and column total C of the row and column containing it, divided by the sample size n. Denoting such an expected number of observations E, these four expected values are:

1st row and 1st column: E=(R×C)∕n=18×28∕40=12.6

1st row and 2nd column: E=(R×C)∕n=18×12∕40=5.4

2nd row and 1st column: E=(R×C)∕n=22×28∕40=15.4

2nd row and 2nd column: E=(R×C)∕n=22×12∕40=6.6

We update Table 11.1 "Baby Gender and Heart Rate" by placing each expected value in its corresponding core cell, right under the observed value in the cell. This gives the updated table Table 11.2 "Updated Baby Gender and Heart Rate".

Table 11.2 Updated Baby Gender and Heart Rate

Heart Rate

Gender

Low

High

Row Total

Girl

O=11 E=12.6

O=7 E=5.4

R = 18

Boy

O=17 E=15.4

O=5 E=6.6

R = 22

Column Total

C = 28

C = 12

n = 40

A measure of how much the data deviate from what we would expect to see if the factors really were independent is the sum of the squares of the difference of the numbers in each core cell, or, standardizing by dividing each square by the expected number in the cell, the sum Σ(O−E)2/E .

We would reject the null hypothesis that the factors are independent only if this number is large, so the test is right-tailed.

In this example the random variable Σ(O−E)2/E has the chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom.

If we had decided at the outset to test at the 10% level of significance, the critical value defining the rejection region would be, reading from Figure 12.4 "Critical Values of Chi-Square Distributions", χα2=χ0.102=2.706 , so that the rejection region would be the interval [2.706,∞) .

When we compute the value of the standardized test statistic we obtain

ΣE(O−E)2=12.6(11−12.6)2+5.4(7−5.4)2+15.4(17−15.4)2+6.6(5−6.6)2=1.231

Since 1.231<2.706 , the decision is not to reject H0 . See Figure 11.3 "Baby Gender Prediction". The data do not provide sufficient evidence, at the 10% level of significance, to conclude that heart rate and gender are related.

Figure 11.3 Baby Gender Prediction

With this specific example in mind, now turn to the general situation.

In the general setting of testing the independence of two factors, call them Factor 1 and Factor 2, the hypotheses to be tested are

H0:The two factors are independent vs. Ha:The two factors are not independent

As in the example each factor is divided into a number of categories or levels. These could arise naturally, as in the boy-girl division of gender, or somewhat arbitrarily, as in the high-low division of heart rate.

Suppose Factor 1 has I levels and Factor 2 has J levels. Then the information from a random sample gives rise to a general I×J contingency table, which with row totals, column totals, and a grand total would appear as shown in Table 11.3 "General Contingency Table".

Each cell may be labeled by a pair of indices (i,j). Oij stands for the observed count of observations in the cell in row i and column j, Ri for the ith row total and Cj for the jth column total.

To simplify the notation we will drop the indices so Table 11.3 "General Contingency Table" becomes Table 11.4 "Simplified General Contingency Table". Nevertheless it is important to keep in mind that the Os , the Rs and the Cs , though denoted by the same symbols, are in fact different numbers.

Table 11.3 General Contingency Table

Table 11.4 Simplified General Contingency Table

As in the example, for each core cell in the table we compute what would be the expected number E of observations if the two factors were independent. E is computed for each core cell (each cell with an O in it) of Table 11.4 "Simplified General Contingency Table" by the rule applied in the example:

E=R×Cn

where R is the row total and C is the column total corresponding to the cell, and n is the sample size.

After the expected number is computed for every cell, Table 11.4 "Simplified General Contingency Table" is updated to form Table 11.5 "Updated General Contingency Table" by inserting the computed value of E into each core cell.

Table 11.5 Updated General Contingency Table

Here is the test statistic for the general hypothesis based on Table 11.5 "Updated General Contingency Table", together with the conditions that it follow a chi-square distribution.

Test Statistic for Testing the Independence of Two Factors

χ2=ΣE(O−E)2

where the sum is over all core cells of the table.

If

the two study factors are independent, and

the observed count O of each cell in Table 11.5 "Updated General Contingency Table" is at least 5,

then χ2 approximately follows a chi-square distribution with df=(I−1)×(J−1) degrees of freedom.

The same five-step procedures, either the critical value approach or the p-value approach, that were introduced in Section 8.1 "The Elements of Hypothesis Testing" and Section 8.3 "The Observed Significance of a Test" of Chapter 8 "Testing Hypotheses" are used to perform the test, which is always right-tailed.

EXAMPLE 1. A researcher wishes to investigate whether students’ scores on a college entrance examination (CEE) have any indicative power for future college performance as measured by GPA. In other words, he wishes to investigate whether the factors CEE and GPA are independent or not. He randomly selects n = 100 students in a college and notes each student’s score on the entrance examination and his grade point average at the end of the sophomore year. He divides entrance exam scores into two levels and grade point averages into three levels. Sorting the data according to these divisions, he forms the contingency table shown as Table 11.6 "CEE versus GPA Contingency Table", in which the row and column totals have already been computed.

TABLE 11.6 CEE VERSUS GPA CONTINGENCY TABLE

GPA

CEE

<2.7

2.7 to 3.2

>3.2

Row Total

<1800

35

12

5

52

≥1800

6

24

18

48

Column Total

41

36

23

Total=100

Test, at the 1% level of significance, whether these data provide sufficient evidence to conclude that CEE scores indicate future performance levels of incoming college freshmen as measured by GPA.

[ Solution ]

We perform the test using the critical value approach, following the usual five-step method outlined at the end of Section 8.1 "The Elements of Hypothesis Testing" in Chapter 8 "Testing Hypotheses".

Step 1. The hypotheses are H0:CEE and GPA are independent factors

vs. Ha:CEE and GPA are not independent factors

Step 2. The distribution is chi-square.

Step 3. To compute the value of the test statistic we must first computed the expected number for each of the six core cells (the ones whose entries are boldface):

1st row and 1st column: E=(R×C)∕n=41×52∕100=21.32

1st row and 2nd column: E=(R×C)∕n=36×52∕100=18.72

1st row and 3rd column: E=(R×C)∕n=23×52∕100=11.96

2nd row and 1st column: E=(R×C)∕n=41×48∕100=19.68

2nd row and 2nd column: E=(R×C)∕n=36×48∕100=17.28

2nd row and 3rd column: E=(R×C)∕n=23×48∕100=11.04

Table 11.6 "CEE versus GPA Contingency Table" is updated to Table 11.7 "Updated CEE versus GPA Contingency Table".

TABLE 11.7 UPDATED CEE VERSUS GPA CONTINGENCY TABLE

GPA

CEE

<2.7

2.7 to 3.2

>3.2

Row Total

<1800

O=35

E=21.32

O=12

E=18.72

O=5

E=11.96

R = 52

≥1800

O=6

E=19.68

O=24

E=17.28

O=18

E=11.04

R=48

Column Total

C = 41

C = 36

C = 23

n = 100

The test statistic is χ2=ΣE(O−E)2=21.32(35−21.32)2+18.72(12−18.72)2+11.96(5−11.96)2 +19.68(6−19.68)2+17.28(24−17.28)2+11.04(18−11.04)2=31.75

Step 4. Since the CEE factor has two levels and the GPA factor has three, I=2 and J=3 . Thus the test statistic follows the chi-square distribution with df=(2−1)×(3−1)=2 degrees of freedom.

Since the test is right-tailed, the critical value is χ0.012 . Reading from Figure 12.4 "Critical Values of Chi-Square Distributions", χ0.012=9.210 , so the rejection region is [9.210,∞) .

Step 5. Since 31.75 > 9.21 the decision is to reject the null hypothesis. See Figure 11.4. The data provide sufficient evidence, at the 1% level of significance, to conclude that CEE score and GPA are not independent: the entrance exam score has predictive power.

Figure 11.4 Note 11.9 "Example 1"

3. Chi-square Table

Last updated